DNS root server FAQ

What are the root servers?

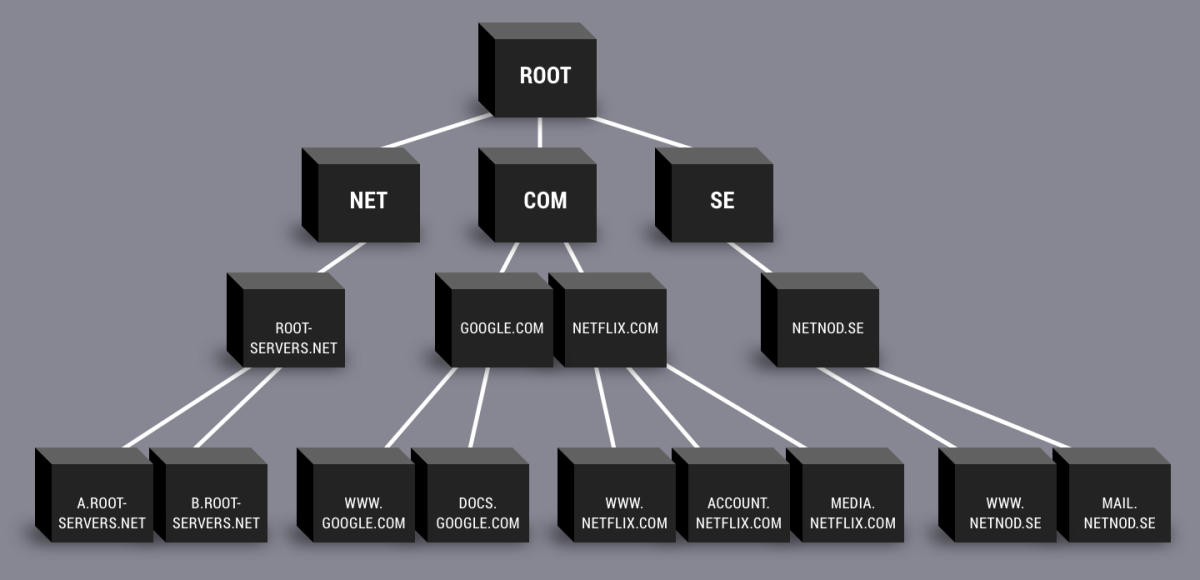

The root servers are the entry points to the Domain Name System (DNS), the distributed database which Internet applications use to look up the numerical IP addresses associated with text-based domain names.

Does the root zone contain all the DNS data?

No. The root servers serve the root zone, which contains information about what Top Level Domains (TLDs) exist, and the addresses of the authoritative DNS servers for each TLD. DNS clients and other servers query the root servers for the TLD information, then go to the appropriate server for details of the domains within that TLD.

Does all Internet traffic go through the root servers?

No. By design, the DNS uses local caching, so other parts of the DNS system query the root servers only periodically to update their caches. Anyway, this process is only about translating a domain name to an address. Once that's done the routing system – which is totally separate – does the rest.

Who are the root server operators?

They are a diverse group of organisations from the private enterprise, non-profit, education, and military sectors. Each of these operators assumed their role in the early days of the DNS (with the exception of the C-root, which passed to the company that acquired the network of the original operator). They are:

- A VeriSign Global Registry Services

- B University of Southern California, Information Sciences Institute

- C Cogent Communications

- D University of Maryland

- E NASA Ames Research Center

- F Internet Systems Consortium, Inc.

- G US DoD Network Information Center

- H US Army Research Lab

- I Netnod

- J VeriSign Global Registry Services

- K RIPE NCC

- L ICANN

- M WIDE Project

Is it true that most of the root servers are based in the United States?

No – this is one of the biggest myths of the DNS. As a historical legacy of how the Internet developed and the pragmatism of early operational arrangements, nine of the 12 root server operators are based in the US. But there are many root servers responding to DNS queries spread all over the world. Which brings us to perhaps the biggest myth of the DNS…

Is it true that there are only 13 root servers?

No, not for a long time. The size of UDP data packets means that there's only room to include the IP addresses of 13 root servers in a single packet. Originally that meant a limit of 13 root server machines, and it gives us the root server names A-M. But thanks to the anycasting technique, each root server address can be mirrored on multiple physical servers in multiple diverse locations. By early August 2014, there were 372 root servers spread across the globe. You can check the up-to-date numbers and locations here: http://www.root-servers.org.

Do all root server operators have multiple servers?

Most do, but not all. It's entirely up to each operator whether to use anycast or not. Currently, there is only one instance of B, whereas there are 145 instances of L. Netnod operates 41 instances of I (i.root-servers.net).

OK, but A is the most important root server, isn't it?

Nope. The lettered names are entirely arbitrary. Every one of the 372 root servers contains and serves exactly the same root zone. That's the point. And they all get the root zone through a distribution infrastructure that is separate from the named root servers.

As a root server operator, can Netnod control the content of the root zone?

No. The content of the root zone is determined as part of the IANA function, subject to ICANN's policy development processes, and is currently maintained by Verisign. Furthermore, the root zone file is digitally signed (using DNSSEC).

But do the root server operators have a say in which new TLDs get added?

The root server operators have no more influence on new TLDs than any other member of the global Internet community. As providers of essential DNS infrastructure, the root server operators – as members of the Root Server System Advisory Committee (RSSAC) – can and do give specialist advice to the ICANN Board about the technical implications of policy developments, but they have no special voice about the specifics of any proposed new TLD.

What is the advantage of having a root server nearby?

Certain DNS activities may get a moderate performance boost if a root server is installed nearby. But remember, these are only a small subset of all online activities, and most of the heavy lifting in DNS takes place in local caches. Furthermore, despite the outraged comments you can find in countless ill-informed online discussions, a local root server does not give its host country any special preference in DNS policy making. The real benefit of installing more root servers in more places is that it makes the DNS overall more robust and resilient.

Are there any parts of the world that do not yet have good service?

It would be misleading to say that any country or region is underserved by the DNS. That said, there are few instances of the root servers in central and northern Africa, western China, and Russia. In general though, the number of root servers says more about physical infrastructure and national regulatory policies in the area than it does about the willingness of operators to set up new sites. Several operators – including Netnod – are always happy to discuss new sites when the local conditions are right.

What does Netnod get out of being a root server operator?

A warm glow… Like all the other root server operators, Netnod spends money to operate a root server (all operators have their own funding models). Of course, we've also built up a lot of unique expertise, which deeply informs our other services. But really, like all the other operators, we do this because we believe it is for the good of the Internet.

Do the root server operators work under contract to ICANN?

No, but the role is far from informal. The operators of F, K, M, and I have exchanged letters of understanding with ICANN (using the same language in the case of all but F). All the operators follow the IETF standards and are guided by common principles. And they coordinate closely, most notably through the RSSAC, which advises the ICANN community and board, and which has published a draft describing what service and performance the Internet community should expect of root server operators. But the specifics of how the operators provide that service are up to the discretion of each operator. A strength of this approach is that it allows for great operational diversity. That means, for example, that a single software or firmware bug cannot bring down the entire system.

What if a root server operator stops operating?

The question of succession is an open and important issue. For example, in 2002 Cogent took over the responsibility for the C-root server when it bought up the assets of the previous operator, PSINet. Despite that, there remains no defined process for how to replace an existing operator with a new one, and it’s a question that the community does need to consider. But it is worth noting that, from a technical perspective, the disappearance of an entire operator is not a particularly big deal. For example, if F were to be completely turned off today, there would still be more than 300 other servers to carry the load.

So, what if a root server operator starts behaving badly?

In theory, a rogue root server operator could pose more problems than a defunct operator, in the sense that an inconsistent fault can be harder to solve than a total failure. But, practically, now that the root zone file is DNSSEC-signed, the scope for improper behaviour is greatly limited.

This seems all very reassuring, but how transparent are root server operations?

For anyone’s who’s interested, a lot of public information is available at http://root-servers.org. Furthermore, operators participate in many public conferences and the RSSAC meets during ICANN meetings. Minutes of RSSAC meetings (including teleconferences) are publicly available on the ICANN website. Obviously there are some specific operational details that cannot be made public for security reasons, but apart from that, information about root servers and the DNS is very accessible.

How big is the root zone file, and does its growth affect DNS performance?

The root zone is still a small file, less than 1 MB. If you feel the need, you can always grab an up-to-date copy from IANA at: http://www.iana.org/domains/root/files. The biggest jump in size of the root zone was a one-off event that came with the introduction of DNSSEC. Perhaps a more important issue is the increasing churn – or rate of change – that comes from adding new TLDs. Of course, it is important to understand how DNS servers and clients will deal with growth and churn in the long term. So, to this end, the RSSAC has published a draft recommending the types of data that root server operators should gather and share to observe long term trends and monitor overall system health.

I want to learn more!

Daniel Karrenberg of the RIPE NCC (the operator of the K root server) has written an excellent document, “The Internet Domain Name System Explained for Non-Experts”, which is available on the Internet Society site (link below). Karrenberg’s document is from some time ago and so some details are now out of date. However, it still provides a clearly explained and useful overview of the DNS and root server system.

• The Internet Domain Name System Explained for Non-Experts

Other good starting points: